It was a snowy evening on the night of February 10th, 1897, and yet the upper echelon of New York’s Gilded Age high society was being dressed in the best of 16th, 17th, and 18th century fashions ready to brave the elements. Why? The ball of the century was about to take place at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel.

America had been in an economic depression for the past 20 years, made worse by the “Panic of 1893” that had all but impoverished roughly 40% of the country. For New York’s elite, the depression had meant less lavish balls. In fact, it had been 14 years since they had a proper banger of a party thanks to Alva Vanderbilt’s famous costume ball of 1883. The ball forced New York’s “400” to recognize them into their ranks. The 400 was a group of old money high society New Yorkers deemed worthy by the Astors, the true monarchs of the time. The Vanderbilts were a part of the nouveau riche and looked down upon by the “old money” families of New York.

By an ingenious plan of not inviting the Astors, Alva secured their attendance. She used the excuse that they had never called upon them at their home, therefore, they had no address to send an invite to. This cornered the Astors, specifically Mrs. Astor, to call upon them in their newly finished “Petit Chateau” when all of the other 400s had been invited. No way could the Astors be the only ones of the 400 who weren’t in attendance. The day after Mrs. Astor visited, they received an invite in the mail.

Another family, the Martins, would not be dealt the same cool shoulder as the Vanderbilts despite them having a similar financial background. Bradley Martin was from a long-established American family in Albany, New York. He descended from the Townsend family. Disturbingly, his grandmother bragged that she was a “double Townsend” since both of her parents were Townsends. It was a different time. His family was financially comfortable but nowhere on the level of the Astors or the Vanderbilts. His future wife’s inheritance, though, would change that. At a Vanderbilt wedding, in which Bradley was in attendance, his attentions were caught by a gorgeous bridesmaid. Her name was Cornelia Sherman.

Cornelia Sherman was born and raised in Troy, and was the daughter of Isaac Sherman. He had started his professional career as a barrel maker, then went into lumber before landing in banking. His good friend Abraham Lincoln advised him to expand his horizons, but for whatever reason, he was content in banking. By the time he died, he had amassed a sizable fortune, all of which was left as inheritance to his one and only child – Cornelia. How much? Over 100 million in today’s money. That money did huge things for the Martins, who had since moved to Manhattan and lived in 2 adjoining Federal-style townhomes on 20th. Despite not being a part of the old Dutch families of New York, they were still welcomed with more open arms than the Vanderbilts. Perhaps it was the right place, right time, since Bradley was a part of the Patriarchs, the precursor to the 400’s, and made up of only 10-12 men originally.

Balls during the Gilded Age were far more than a party, they were truly an important part of society. Think of it as 19th-century speed dating; if you had a son or daughter whom you wished to introduce into society, you would do so at a ball. Very likely, this was one of the very few ways in which they would be able to meet and find a love match. Society etiquette of the day dictated that most men’s outings were to be with other men, whether that be at work or various clubs, whereas women’s outings, if they were of age, would have been limited to philanthropic efforts and salons with other women. There would not have been a lot of random meeting of available men and women during this time, so balls were a place for people to meet, make connections, plot society moves, and so forth. These balls were most often held at home, and the Martins were no stranger to hosting. It’s said that some of their balls were so large that they had to erect tents outside their adjoining townhomes to accommodate their guests until eventually tearing down some of the walls inside the home to connect them in a ballroom.

The impetus for the Martins to throw their ball in 1897 was not, in fact, to match their children. Their daughter, also named Cornelia, had already secured a quite enviable marriage to William George Robert, Fourth Earl of Craven, an Englishman who helped their society, credit much as the Vanderbilts’ daughter Consuelo’s marriage to Charles Spencer-Churchill, 9th Duke of Marlborough, helped them. Their wedding took place at Grace Church in 1893, which sent a statement to the community that they were not just rich but their family was now connected to the English aristocracy. So why then spend the nearly 12 million it would cost for their ball in 1897? Would you believe me if I said it was for charity?

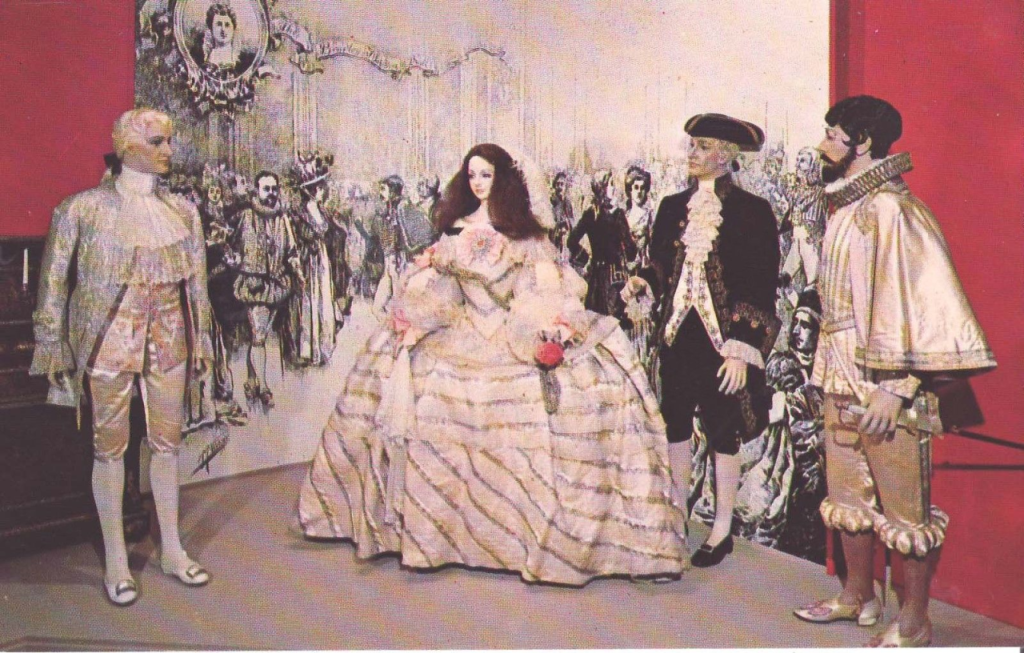

Even though the depression that the majority of the country was suffering wasn’t affecting the Martins, they were sympathetic to the needs and struggles of those less fortunate so they decided to do something about it. Well, in their own way. In an event that would rival the famous ball of 1883, the Martins planned a costume ball to be held on Feb. 10th, 1897 at the Waldorf Astoria and requested the guests come dressed in the best of the 16th, 17th, and 18th royalty. They strategically sent out invites nearly last minute knowing that if they did so, the 1,200 invitees would be left with not enough time to send for costumes in Paris, which meant they would need to employ the services of local seamstresses and tailors, ensuring money was going directly into the hands of the people who needed it. Additionally, they employed hairstylists and costumers to be in attendance in 15 different dressing rooms for their attendees to get touch-ups when they arrived at the ball. Their intentions were good and money was raised for the poor, but it doesn’t mean the ball didn’t come under scrutiny. Famously, JP Morgan’s own Reverend, Reverend Dr. Rainsford, preached from the pulpit that if they really wanted to help the poor, they would take the money they were spending on a party for the rich and donate it. A fair point.

Some of the most entertaining bits of information to come out of the ball’s highlights are tales of the inconvenience the attendees’ costumes created. Most came dressed as kings and queens, the men often having a sword on their side, not something men of this era were used to, which caused a lot of embarrassing fumbling about. Women who came dressed as Georgian and French ladies of the court of the 18th century had a hard time maneuvering about with their wide-hipped gowns. Indeed, the best story is that of the man who came dressed as a full-blown knight, armor and all and ended up falling over because the suit of armor was so heavy. Cornelia may have been the true belle of the ball though, appropriate since this was her brainchild, and she did indeed have the ballroom decked out to look like Versailles, for upon her neck she wore two of Marie Antoinette’s bracelets that she’d turned into chokers. Just a sampling of the mass amount of French Crown jewels the Martins owned, many of which are now on display at the Louvre.

125 tables were set up and adorned with thousands of dollars’ worth of flowers from around the country to accommodate the dinner service held in the wee hours of the morning and even to later serve breakfast in case anyone was still around and famished from a night of revelry. The night played host to everyone who was anyone in New York at the time, even including people that others may have overlooked, such as artists and performers. The amount of pure wealth worn on the bodies of people in attendance created such a security risk that the future President, Theodore Roosevelt, then head of the Police Commission, dispatched 200 police officers to guard the outside of the ball as well as to dress up and secretly wander the party to make sure no threats arose.

The ball was exactly the success that the Bradley-Martin’s had hoped for, the Buffalo Weekly Express even quoting in their article on the event the following day stating;

All great social functions of the past in this town were eclipsed. Even the Vanderbilt ball of 1883, which, until tonight, threw all other affairs of the kind into dim shadow, will now be rated but second-class.

Buffalo Weekly Express

Somewhere along the line a rumor started that the ball was not received well. Perhaps it was because it was excessive and despite the good intentions, was seen as a flaunting of the wealth most Americans were greatly without. The Bradley-Martin’s would return to the UK, not because they were run out of town but because they always would return to the UK to holiday in their many estates. The legacy left by this ball is an insight into the Gilded Age of New York, a time where high society men and women adorned themselves in the jewels of European monarchs, who schemed their way to the top and who married their offspring off to more noble blood in the hopes of gaining credibility. In the scope of American history, it is but a small blurb of time but nonetheless, a fascinating one.